Recently, I got a link to a Zoom meeting that ended like this:

DQMAAAAUCGxioRZBeXVxb2Y5U1F4ZTh2ODFaTFVBblVBAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

I feel it truly captured the head-desk vibe of our current times. And it’s this vague aesthetic I want to bring to today’s blog. So come one, come all, on a journey with me through the eternal frustration and confusion of the artistic soul.

Being a writer is a funny old thing. It’s a bit like becoming a parent, or being a woman who happens to exist. Everyone has an opinion on the correct way to do it, and rest assured you are not doing it right. Everyone has some serious views about your value, and rest assured it’s not quite enough. And everyone will let you know these things all the time on repeat forever and ever amen.

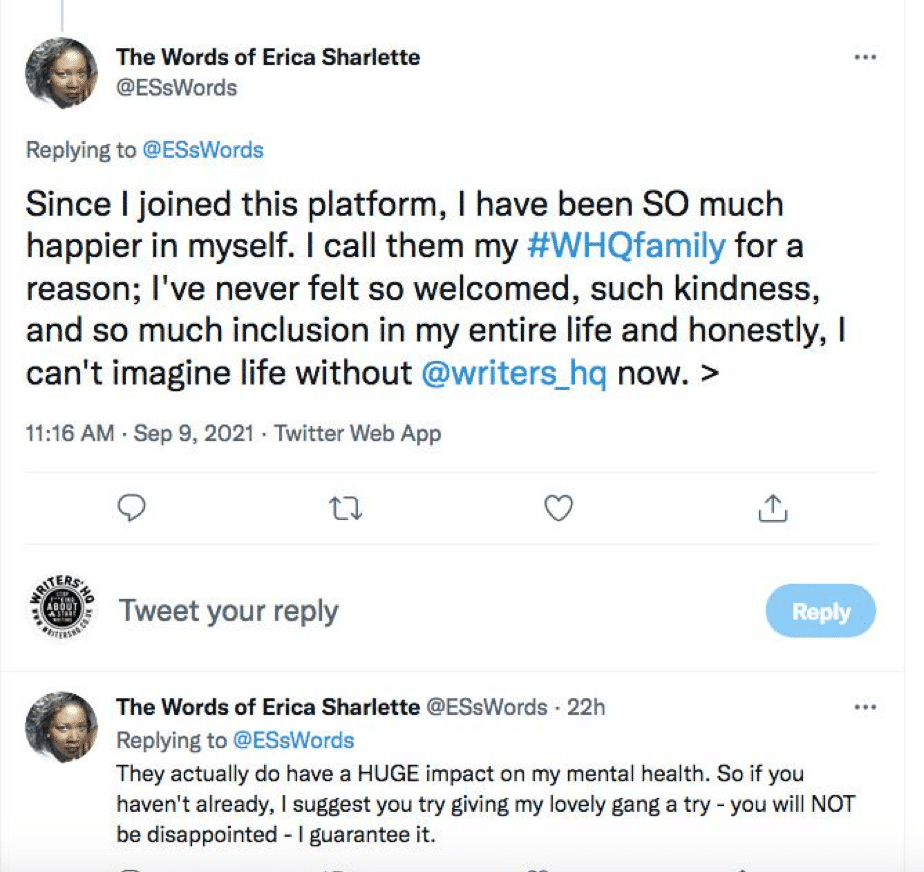

For example, I co-founded Writers’ HQ. A successful writing organisation with tens of thousands of humans in our community with non-stop publishing wins, and people who say things like this:

And I’ve spent my entire adult life writing for a living, like actually being paid for it, with money. An occupation which just about pays for a mortgage and two kids, albeit precariously at times.

But because I haven’t written a bestseller, I am not considered a successful writer.

That’s what the external voices say. Oh, your hobby. How… cute? What’s your day job outside of your little book club? Are you a real writer? Maybe one day you’ll be good enough. Why don’t you just write a bestseller? Oh I’m not writing a novel either! Hahahaha etc.

But.

For ostensibly successful writers — that is, those whose words are in print and sold at airports, or who are read through the ages — it’s seen as a noble and romantic and intellectual and lauded occupation. An important one. After all, the stories that explain our world are the common language with which we understand it. Side note: we’ll come back to that definition of successful shortly.

Here’s the big question: how do those successful writers get to be successful?

Well, historically it was something like this:

– Starving artist finds wealthy benefactor (or starving artist continues to starve).

– Artist (maybe starving, maybe not) dicks around producing nothing of note for many many many many many years but experiments freely and with wild abandon and no limitations or expectations.

– One morning, artist wakes up and realises they’ve produced something that’s Good, Actually.

– Artist’s work goes public, receives criticism and praise OR artist dies and is posthumously lauded (we don’t recommend this one too much tbh. No fun).

– Rinse, repeat.

In the present time, point 1 is often (but not always) replaced with a university place or other creative writing courses, undertaken in a full or part time capacity around other responsibilities. It’s not so much the teaching that goes on (although much of it is excellent) as it is the time and space to do the thing in an environment where the thing is encouraged, accepted, loved and supported.

From this we can deduce that the path from Hello I’m A Person to Hello I’m A Successful Writer necessarily involves a period of development in which the writer is allowed to experiment freely and without expectation and learn all the things and read all the things and ponder all the things. They are allowed to, if you will, languish in the arts and humanity departments of the universities of their brainz.

Here’s an important caveat. Not all the artists doing the experimenting will go on to become “successful” artists. Some will decide being an artist is definitely not for them. Some will go on to teach and support other artists. Others will never quite make art the way they want and be frustrated forever. Some will go on to write a legendary episode of Eastenders (“You’re not my muvvahhhh!”). Some will be perfectly happy doing whatever it is they’re doing without any kind of external recognition or validation. Some will go on to paint the Sistine Chapel. Some will get external recognition or validation way beyond their actual ability. Some will go on to write an obscure short story that four people read but really, deeply appreciate. The possibilities are endless and varied and valid and all are important, at the very least to the person to whom the possibilities are happening.

Much like a salesperson needs to harass 100 people to make one sale, it takes 100 artists to produce one piece of work of staggering, heartbreaking beauty. (Numbers are completely made up, obviously).

All of which is to say, everything contributes to everything. Your artistic endeavours might not be The Big One, but they may well influence the person who has The Big One. Your story might be read by four people, one of whom might be inspired enough to write a story read by 40,000 people. All creators, all artistic projects, are part of a larger, grander, vital web of arting and storying and humaning. Take away any part of that web and what happens? You get homeless, hungry art-spiders, that’s what, and no beautiful dew-speckled web to marvel at in the early morning light.

AND ANOTHER THING

The definition of success that claims a successful writer is the writer who has published a bestseller is a definition driven by… fanfare please… capitalism. The successful ones under this system are the ones who make the money. But at the same time, the need to make the money means publishers will only publish increasingly safe books, which in turn means the urge to be seen as successful forces us to write to a perceived notion of what will sell, which creates exactly the opposite environment in which we can truly create. See above. (And obvs exceptions here for authors like Kazuo Ishiguro or David Mitchell who write gloriously batshit stuff, but are only permitted to do so after proving their financial chops with a handful of bestsellers). This is why writers who write for any other reason than bestseller-dom are belittled (not making money! Pointless!), but writers who do the bestseller thing are romanticised (making the money, the lovely cash money!), despite the fact that to get to the latter you have to first be and do the former. Cross my palms with gold-pressed latinum and stick a fork in me. I. Am. Done.

So what is the take away from this extraordinary rant that was supposed to be a stupid meme-based blog containing this:

The take away is this:

1. Your success is not measured by external validation because our measures of external validation are bunt.

2. Your success is measured by your artistic development and only you can judge that based on what you set out to do in the first place.

Now go write.